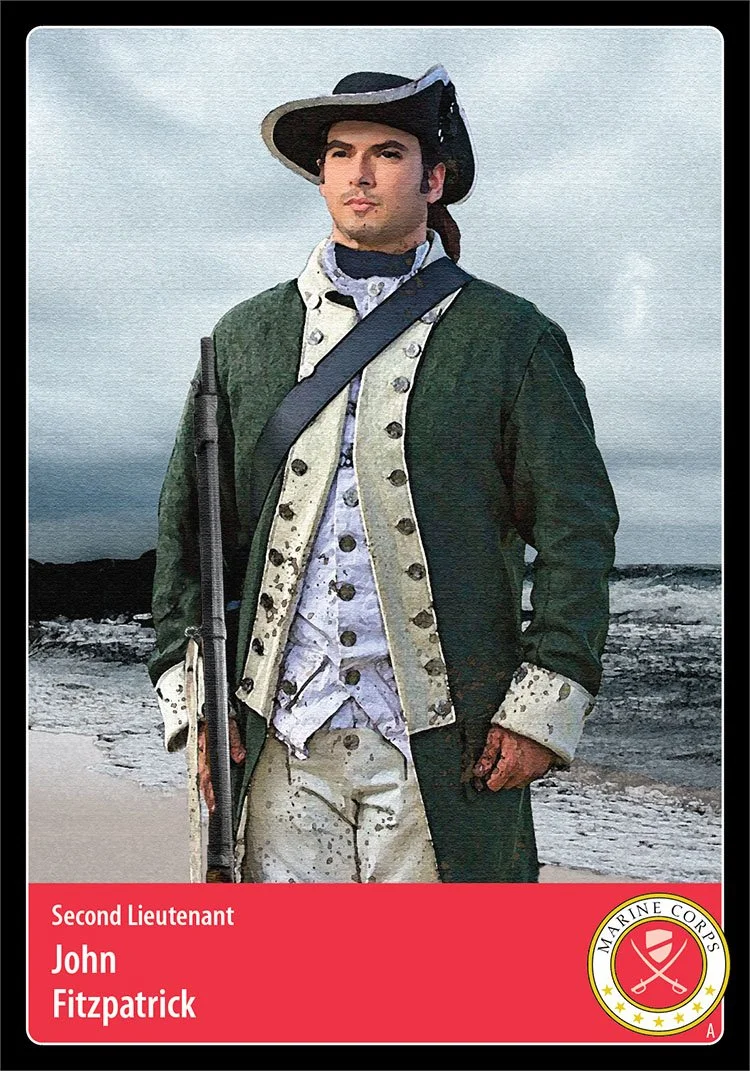

Hero Card 264, Card Pack 22

Artist's impression by Craig Du Mez

Hometown: Philadelphia, PA

Branch: Continental Marines

Unit: Continental Navy flagship Alfred

Date of Sacrifice: April 6, 1776 - KIA at sea, near Block Island, Rhode Island

Age: unknown

Conflict: Revolutionary War, 1775-1783

On May 10, 1775, a year before the 13 English colonies in America declared independence from the British Crown, representatives from each colony reconvened at the Pennsylvania State House (later renamed Independence Hall) in Philadelphia. The Second Continental Congress faced increased urgency, as the first shots of the American Revolution had been fired at Lexington and Concord, Massachusetts.

On June 14, 1775, the Congress voted to create a Continental Army to protect the rights of colonists against the increasing presence of British troops. A day later, General George Washington of Virginia was appointed as the new army’s Commander-in-Chief.

The British Royal Navy already had 24 ships committed to North America, and the number would grow dramatically as hostilities escalated (by June 1776, over 500 transport ships and 70 British warships sailed into New York Harbor in preparation to capture the city).

On October 13, 1775, the Continental Navy was born as the Congress approved “a swift sailing vessel, to carry ten carriage guns, and a proportionable number of swivels, with eighty men, be fitted, with all possible despatch [sic], for a cruise of three months…”

The Continental Marines

A month later, on November 10, 1775, the Continental Congress passed a resolution “That two battalions of marines be raised…”—creating what is now the United States Marine Corps.

Gen. Washington disagreed with the resolution, as it would draw troops away from his already depleted army. The Congress conceded, commissioning Samuel Nicholas as the first American Marine officer and requiring him to raise the two Marine battalions from new recruits, rather than from Washington’s army.

In his book, Washington’s Marines: The Origins of the Corps and the American Revolution, 1775-1777, author Jason Q. Bohm recounts those first Marine recruitment efforts:

Drummer boys marched through Philadelphia streets, playing drums adorned with decorative paintings to draw potential recruits into the public meeting houses. One such instrument had a painting of a coiled rattlesnake with the phrase “Don’t Tread on Me” etched below it. On the day of his appointment, Capt. Robert Mullan, the owner of the popular Tun Tavern, enlisted two brothers to be his drummer and fifer, hoping to use their music to draw potential recruits into his establishment. Tun Tavern, on the east side of Philadelphia’s South Walnut Street, became a focal point of Marine recruitment; it has gone down in history as the accepted birthplace of the United States Marine Corps.

Second Lieutenant John Fitzpatrick was one of those first recruits from Philadelphia. Within weeks of the birth of the Continental Marines, the Continental Congress received word that large stores of gunpowder and cannon had been established in two British forts—Fort Nassau and Fort Montagu—in the city of Nassau, New Providence Island, in the Bahamas. A British regiment assigned to protect the forts had been called up to Boston, Massachusetts, to reinforce the British garrisons there.

First Mission

With the rushed construction of frigates, conversions of merchant vessels, and hiring of privateers, the young Continental Navy received orders to sail a fleet of 8 vessels under the command of Commodore Esek Hopkins. Their mission was to engage the British fleet in Chesapeake Bay, then sail to Rhode Island and attack British Forces there, if wind and weather permitted.

Led by Capt. Samuel Nicholas, more than 200 Continental Marines boarded the 8 vessels. The fleet consisted of the 24-gun Alfred (flagship), the 20-gun Columbus, the 14-gun Andrea Doria, the 14-gun Cabot, the 12-gun Providence, the 10-gun Hornet, the 8-gun Wasp, and the 8-gun Fly.

Captain Hopkins’ fleet didn’t come across the British ships that had been devastating the east coast. With winter setting in, it was expected that Hopkins would sail southward to defend the southern colonies’ shores.

The lightly defended armory stores in the Bahamas presented a tempting target. Whether Capt. Hopkins sought personal glory or wanted to seize a rare opportunity to capture gunpowder and cannons—resources desperately needed by Continental forces—he decided to sail for New Providence Island in the Bahamas, and the two British forts in Nassau.

First Amphibious Assault

Just before noon on March 3, 1776, 230 Marines and 50 seamen under Capt. Nicholas’s command jumped from longboats into the surf, about 2 miles east of Fort Montagu. According to Marine Corps University:

Carrying tower muskets, cartridge boxes, bayonets, and wearing a variety of civilian coats, white vests and breeches, and hats, the Marines gathered ashore in preparation for their march toward the fort. The Continental Marines, in their first amphibious assault, captured Fort Montagu in a battle as “bemused as it was bloodless.” After resting the night in their prize, the invasion force completed the job of securing the island by taking Fort Nassau and arresting Governor Montfort Browne the next morning.

After token resistance, the British negotiated a ceasefire and, in the dark of night, managed to slip 162 barrels of gunpowder out from under the Americans’ notice. Angered by the deception, Capt. Hopkins had the forts and the town stripped bare of cannons and ammunition before departing with his fleet.

Despite the embarrassment of losing the 162 gunpowder barrels, the raid was considered a huge success. Not a shot was fired, and the Americans had taken both forts and the city of Nassau. Log books show that the fleet captured 24 remaining casks of gunpowder, 88 guns, 15 mortars, over 16,500 shells of shot, and 38,240 pounds of round shot.

Hopkins faced both praise for the bold action and questions about whether he had disobeyed orders. Whatever the truth, his fleet delivered much-needed hope to the artillery-starved Continental Army.

First American Marine killed in battle

The fleet had more success during its return north, freeing captured ships from the British. In early April 1776, Hopkins’ fleet spotted and captured the British schooner Hawk off Rhode Island’s Block Island. Adding the bomb brig Bolton to their list of victories, by April 5, 1776, the total stood at 8 enemy and loyalist ships captured.

In the early hours of April 6, 1776, the fortunes of that first Marine battalion would change in an unexpected encounter with the British sloop Glasgow. The History and Museums Division of the U.S. Marine Corps captures the confrontation’s details in A Pictorial History, The Marines in the Revolution:

The voyage northward following the raid on New Providence was routine. An hour into the midnight watch on 6 April 1776, however, the situation changed; two unidentified sails were sighted to the southeast. All hands were called to quarters as the distance closed, and it became clear that one of the vessels was a ship of considerable size. She proved to be the Glasgow, a 20-gun ship of the Royal Navy, accompanied by her tender.

On board the Alfred, Marine Captain Samuel Nicholas was roused out of bed and his company ordered to assemble. Once collected and outfitted for action the Marines were divided into two groups; one group under First Lieutenant Matthew Parke taking the main deck, and the other under Captain Nicholas and Second Lieutenant John Fitzpatrick manning the quarter deck.

As the Cabot reeled away under the weight of the Glasgow’s cannon, the Alfred was brought into action. In one of the first exchanges, Captain Nicholas’ second lieutenant, John Fitzpatrick, was felled by a musket ball. “In him,” Nicholas later wrote, “I have lost a worthy officer, sincere friend and companion, that was beloved by all the ship’s company.”

Four were lost and seven wounded aboard the Cabot, six lost and six more wounded aboard the Alfred.

Those first Marines—including 2ndLt. John Fitzpatrick of Philadelphia—gave their lives for their country, three months before it was officially born with the signing of the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776.

Sources

Artist’s Impression: Craig Du Mez

Jason Q. Bohm, Washington’s Marines: The Origins of the Corps and the American Revolution, 1775-1777

History.com: Birth of the U.S. Marine Corps

Marine Corps University: A Chronology of the United States Marine Corps, 1775-1934

Marine Corps Association: The First of Many

American Battlefield Trust: “Resolved, That two Battalions of marines be raised”

John D. Gresham, Defense Media Network: Revolutionary War: Battle of Nassau

Jeff Dacus, Journal of the American Revolution: Gunpowder, the Bahamas, and the First Marine Killed in Action

Eric Sterner, Journal of the American Revolution: Engaging the Glasgow

Marine Corps University: A Pictorial History, The Marines in the Revolution

We Are the Mighty: A tiny Marine Corps’ big successes in the Revolution