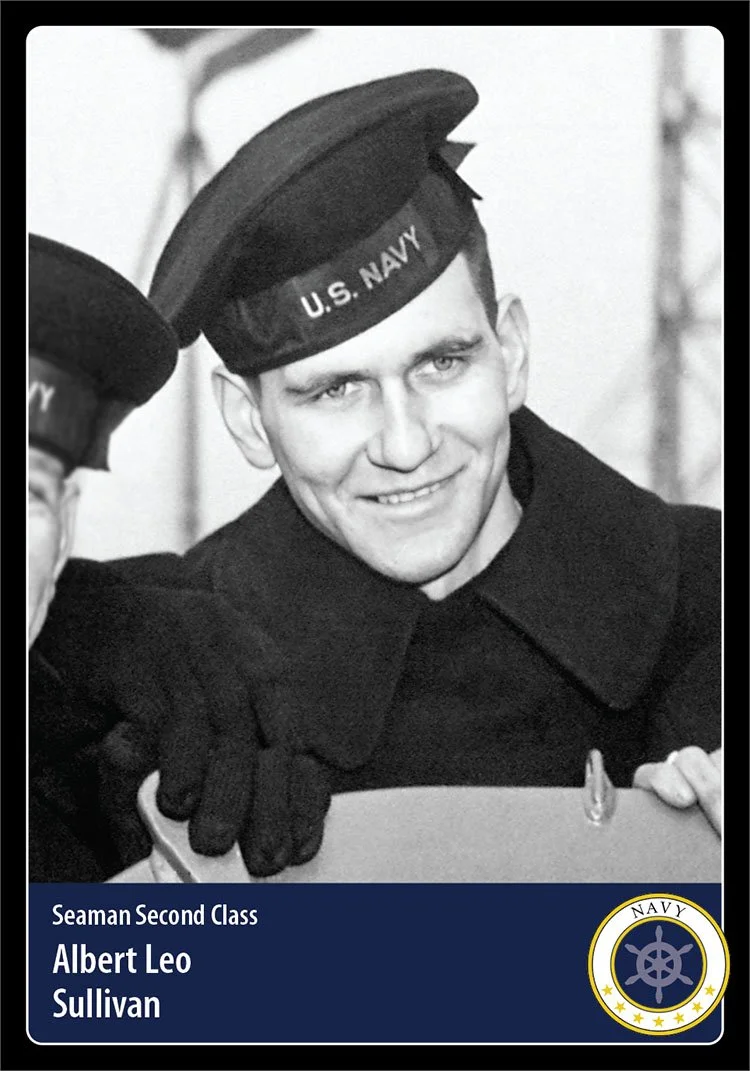

Hero Card 285, Card Pack 24

Photo credit: National Archives NAID: 535944 (digitally enhanced), Public Domain

Hometown: Waterloo, IA

Branch: U.S. Navy

Unit: USS Juneau (CL-52)

Military Honors: Purple Heart

Date of Sacrifice: November 13, 1942 - KIA at sea, near San Cristobal, Solomon Islands

Age: 20

Conflict: World War II, 1939-1945

NOTE: Because the five “Fighting Sullivan brothers” share the same background and fate, the five biographies (Heroes 281-285) contain the same text.

Family loyalty was a way of life for the six Sullivan children. Parents Tom and Alleta raised George, Francis (Frank), Genevieve, Joseph (“Red”), Madison (Matt), and Albert (Al) in Waterloo, Iowa. The Sullivans were a working-class Irish American family.

Their father, Tom, worked for the Illinois Central Railroad between Waterloo and Freeport, Illinois. Mother Alleta struggled to maintain order, with her unruly five boys developing a reputation in Waterloo for being “notorious rascals,” according to the Irish Independent.

Tom’s work regularly took him away from home. He struggled with alcoholism and Alleta “was a highly strung woman barely able to cope with her brood.”

The Sullivan children grew up during the Roaring 20s and the Great Depression, a global economic downturn lasting from 1929 to 1939. Tom’s railroad job provided steady work and an above-average income given the hard times and their distance from a larger city.

According to John R. Satterfield in his book, We Band of Brothers, The Sullivans and World War II:

George Sullivan led his siblings from the beginning. George was chubby in his early years, prompting the nickname “Georgie Porgie” that stuck with him for some time. Frank was a more serious and aggressive youngster, but not a leader like George. Eugene, third of five, was an adaptable, endearingly goofy fellow, consistent with his middle ranking in the pecking order. But he also stood out physically, with his red hair and freckles…and a nickname, Red, also stuck. Matt, brother number four, was quiet, reminding everyone the most of his father. Matt also did better in school than the others, liked music and was crazy about dancing. Al, the youngest of the brood, was a charmer, friendly with everyone, and never seemed to resent his baby-of-the-family status.

At different times, the Sullivan children were enrolled at St. Mary’s Catholic School and at the local public schools. Paying for tuition and textbooks at a parochial school was likely too expensive, once all of the children reached school age.

Average students at best, all the Sullivan boys left school before graduating. George and Frank quit school after the 8th grade at East Junior High—with Frank leaving after having to repeat the 8th grade in 1929. Red left school after finishing the 9th grade in 1936. Matt completed 10th grade at Waterloo East High School, quitting in 1938. That same year, Al dropped out of the 9th grade at East Junior High.

As young men, all five brothers found work at Waterloo’s Rath Packing Company, which at the time was the largest meat-packing plant in the United States.

Navy service

George and Frank, the two eldest, traveled to the Navy Recruiting Station in Des Moines, Iowa, and enlisted in the U.S. Navy on May 11, 1937. As Apprentice Seamen, they were sent together to the Naval Training Center in San Diego, California, for recruit training.

By September of that year, George and Frank were upgraded to Seaman Second Class, and were both assigned to the destroyer USS Hovey (DD-208).

Hovey conducted operations along America’s west coast, around the Panama Canal, and in the waters off Hawaii. According to the U.S. Navy, Hovey was converted to a minesweeper in November of 1940. After intensive training she sailed for duty at Pearl Harbor on February 4, 1941.

George rose to the rank of Gunner’s Mate Third Class, and Frank to Seaman First Class. After completing their four-year enlistments, the two brothers were honorably discharged in May of 1941.

War hits home

Seven months after George and Frank completed their service and returned to Waterloo, the Empire of Japan launched a surprise attack on the U.S. Navy’s Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii on December 7, 1941.

Not only was their country attacked on that day. Having just returned home from Pearl Harbor, George told the The Democrat and Leader, “…that’s just where we want to go now. A buddy of ours was killed in the Pearl Harbor attack—Bill Ball of Fredericksburg, Iowa.”

Their friend, Seaman First Class William V. “Bill” Ball, had served on the USS Arizona (BB-39), which exploded and sank to the bottom of Pearl Harbor.

The Sullivans wasted no time. Within weeks, on January 3, 1942, the five brothers travelled to the Navy recruiting station in Des Moines to enlist.

Serving together

Al, the youngest, was the only one of the Sullivan brothers with his own family. At age 17, he’d married Katherine Rooff, and the two later welcomed a son, James. At the time, the Navy was not recruiting married fathers. Katherine’s permission would be required for Al’s enlistment.

From the start, the Sullivan boys gave their recruitment officer problems. Despite the urging of Navy superiors for the boys to be divided for assignment, the Sullivans insisted that if the Navy didn’t accept Al’s enlistment—and assign them to the same ship—the other four would not enlist. The Navy granted their request.

According to the Sullivan Brothers Iowa Veterans Museum:

The public relations possibilities of having five brothers enlist together, and serving on the same ship, wasn’t lost on the Navy. Word was spread. The five brothers appeared in newsreels and publicity photos. They were feted at heavyweight boxing champion Jack Dempsey’s restaurant before the Juneau embarked from the Brooklyn Navy Yard in New York Harbor. Pictures of the five handsome brothers—all bachelors except Albert, the youngest—circulated around the country.

After training together at Naval Station Great Lakes in northern Illinois, the five Sullivans were assigned to the USS Juneau (CL-52), an Atlanta-class light cruiser. Juneau was commissioned in February 1942 and spent its first months operating off the U.S. Atlantic coast and in the Caribbean Sea.

After several task force assignments in the Atlantic, Juneau was sent to the Pacific Theater of Operations. They crossed through the Panama Canal in mid-August 1942 and proceeded west.

After an important American victory over the Japanese in the Battle of Midway Island in June 1942, the Japanese turned their attention toward building an air base on Guadalcanal, in the eastern end of the Solomon Islands chain. U.S. Marines landed on Guadalcanal in August, capturing the partially completed air strip. The victory was only the beginning of a seven-month land, sea, and air battle for control of the strategic island.

The Juneau disaster

With Japanese and Allied forces fighting for control of Guadalcanal, Juneau was sent in as part of a convoy. Both sides were sending in troop reinforcements, food, ammunition, and other supplies in hopes of gaining the upper hand.

In the early morning hours of November 13, 1942, a Japanese convoy attacked the American ships. Juneau was struck on the port side by a torpedo. The explosion buckled the deck, shattered the fire control computers, and knocked out power. Juneau somehow limped back to the other surviving American vessels.

The Naval History and Heritage Command describes what happened next:

About an hour before noon, the task force crossed paths with Japanese submarine I-26. At 1101, the submarine fired three torpedoes at San Francisco [CA-38]. None hit that cruiser, but one passed beyond and struck Juneau on the port side very near the previous hit. The ensuing magazine explosion blew the light cruiser in half, killing most of the crew.

Four of the Sullivan brothers were lost in the explosion. George, who had been wounded in the first attack, had just returned to duty near the depth-charge racks on the fantail of the ship. He survived the blast, along with at least 100 others.

Help was slow to arrive. Many were too injured to survive. Only 10 would make it through the next seven days of exposure, dehydration, and shark attacks.

One survivor, Gunner’s Mate Allen Heyn, recalls George calling out his brothers’ names, becoming increasingly delirious. “George Sullivan said he was going to take a bath. He took off all his clothes and got away from the raft a little way.” Heyn said that George was lost to a shark attack.

Awaiting word

Thomas and Alleta Sullivan were desperate for news of their five sons. In January of 1943, Alleta wrote to the Bureau of Naval Personnel:

I am writing to you in regards to a rumor going around that my five sons were killed in action in November. A mother from here came and told me she got a letter from her son and he heard my five sons were killed. It is all over town now, and I am so worried.

…If it is so, please let me know the truth.

On a cold January morning, the Navy dispatched three representatives to the Sullivan home to bring the worst imaginable news. Tom, a man of few words, met them at the front door and said, “Which one?” The response from Lieutenant Commander Truman Jones was, “I’m sorry. All five.”

Stunned, Tom asked the men to wait while he went to get Alleta. With the family present, Jones carried out his duty. “The Navy Department deeply regrets to inform you that your sons Albert, Francis, George, Joseph, and Madison Sullivan are missing in action in the South Pacific.”

After taking a few moments to grasp the news, Aletta recounts, “Dad turned to me. He was due at work…He looked at the clock and reached for his dinner pail. His train was leaving in half an hour. He said, ‘Shall I go?’ I knew that his train was carrying war freight. If the freight didn’t reach the battle fronts in time, it might mean more casualties. Dad holding up the train might mean that other boys would die; that other mothers might have to face such grief needlessly, so I said…‘It’s all right, Tom. It’s the right thing to do. The boys would want you to…there isn’t anything you can do at home.’”

Knowing the unlikelihood of the Sullivan brothers’ survival, President Franklin D. Roosevelt replied in a January 13, 1943, letter, which reads in part:

As Commander-in-Chief of the Army and Navy, I want you to know that the entire nation shares in your sorrow. I offer you the condolences and gratitude of our country. We who remain to carry on the fight must maintain spirit, in the knowledge that such sacrifice is not in vain.

I send you my deepest sympathy in your hour of trial and pray that in Almighty God you will find the comfort and help that only He can bring.

Along with most of Juneau’s crew, the five Sullivan boys were at first reported missing and presumed dead. Not until August 1943 did the Navy officially acknowledge that the missing crewmembers of the Juneau were killed in action.

The Navy referred to the deaths of the five Sullivan brothers as “the biggest blow to any one family in U.S. wartime history.”

Honoring “The Fighting Sullivans”

The loss of the five Sullivan brothers was used by the Navy and by Hollywood as a rallying point for the nation’s war effort. In 1944, the movie “The Sullivans” (later renamed “The Fighting Sullivans”) was released by Twentieth Century-Fox and was nominated for an Oscar.

Genevieve Sullivan enlisted in the Naval Reserve as a Specialist (Recruiter) Third Class. Along with her parents, she visited more than two hundred manufacturing plants and shipyards.

According to the Navy, the Sullivans “…visited war production plants urging employees to work harder to produce weapons for the Navy so that the war may come to an end sooner.” By January 1944, the three surviving Sullivans had spoken to over a million workers in sixty-five cities and reached millions of others over the radio.

On 4 April 1943, Alleta Sullivan christened a new Fletcher-class destroyer, the USS The Sullivans (DD-537). In January 1944, the parents accepted her sons’ five Purple Heart medals.

A second vessel, an Arleigh Burke-class guided-missile destroyer—USS The Sullivans (DDG-68)—was commissioned by the Navy on April 19, 1997.

Each brother has a memorial cenotaph in Arlington National Cemetery, and their names are inscribed on the Tablets of the Missing at the Manila American Cemetery and Memorial in the Philippines.

Early on the morning of March 17, 2018, the wreck of the Juneau was found by the Research Vessel Petrel, some 13,000 feet below the surface of the Pacific. The USS Juneau was discovered—fittingly for the Fighting Sullivans—on St. Patrick’s Day.

Sources

Naval History and Heritage Command: The Sullivan Brothers

Naval History and Heritage Command: The Sullivan Brothers: Transcripts of service

The Democrat and Leader, Jan. 4, 1942: Sullivan Brothers, All Five of ’Em, Join Navy

Grout Museum District: The Sullivan Brothers: 80 years later, ‘people do care, and people do remember’

U.S. Naval Institute: Remembering the Sullivans

Jack R. Satterfield: We Band of Brothers: The Sullivans and World War II

Irish Independent, Aug. 23, 2003: Meet the Sullivans: a real band of brothers

Military.com: The Sullivan Brothers

Naval History and Heritage Command: The Sullivan Brothers: Report on Loss of USS Juneau (CL-52)